When we hear the word ‘privacy’, we might think of tracking, cookies or Cambridge Analytica. We might even think of a recent security breach that’s released millions of user’s data into the wild.

Privacy has a different meaning for everyone. But as a website owner, what does a privacy-focused website look like and what do you need to consider to build one?

Cookies

Let’s start with cookies, the device websites and services use to collect data about how users behave online. They fuel all sorts of online activity, from basic functionality like logging in, to the tracking that underpins the behavioural advertising industry.

Many marketing and analytics tools rely on cookies to function. They track users as they browse the web, then feed that data back to the original service (Google Analytics, Facebook Pixel, etc).

Under PECR legislation, only functional cookies can be set before a user opts-in. Cookies for marketing and analytics can only be set after a user chooses to allow them.

Leaving aside ethical issues around tracking, many websites have a poor approach to cookie opt-in. It’s common to see sites that:

Force users to accept all cookies (“By continuing to use this site you agree to our use of cookies...”)

Set non-essential cookies before a user opts-in

Use dark patterns in cookie banners, making it hard for users to opt-out

Take the MacRumors.com cookie banner, for instance. Once you open the options, it’s not immediately clear which button you need to press to opt-out of cookies:

Data and (vanity) metrics

Site owners and marketers have grown used to being able to access an endless stream of data about users. This is a by-product of several factors:

The metadata devices/apps broadcast and collect about users

Old technologies and approaches that are now baked into modern systems

Humanity’s seemingly insatiable desire for data

Much of this data is collected without user’s awareness or consent. The spy pixels that our emails contain are a great example of this.

To enable read receipts in email, services embed a tracking pixel that can report:

When a user opens an email

Where they were when they opened it

How many times they opened it

What device was used to read it

The links a user clicked in the email

How many times each link was clicked

Users are rarely told about this data collection, let alone given an opportunity to opt-out. If they unsubscribe and revisit an email, the data collection continues.

What’s surprising is how relatively unknown this is outside the tech and marketing worlds. Especially as email addresses are so intrinsically linked to their owners.

Prioritising useful metrics

This data is collected to track two email statistics:

Open rates

Click rates

Given the increasing number of services that block tracking pixels, click rates are the only useful indicator of engagement – data that can be collected without building a logbook of every recipient’s email behaviour and location history.

This data collection in emails is representative of other areas: it’s collected because it’s available. After tasting this forbidden fruit, it can be hard to kick the data collection habit.

If we’re serious about pursuing privacy-friendly choices for users, we have to question the data we collect and why.

Which metrics are useful to us? How can we collect this in a manner that doesn’t invade our users’ privacy?

Website data collection

Email is a good example of unnecessarily broad data collection because it combines:

A lack of awareness about the surveillance taking place, especially amongst users (the surveilled)

A widespread and ongoing privacy-invasive practice

A collective pursuit of a low-value data (open rates)

The limitations of old web technology (the pixel can’t be removed when a user unsubscribes)

But we can bring this thinking back to the websites we run.

For instance, Google Analytics has been the dominant analytics service for many years. It’s free, powerful and easy to install, but not without issues:

It requires cookies to work

It’s complex software

Visits won’t be collected for users of ad-blockers or certain browsers

The data feeds the surveillance capitalism model

Alternative analytics

In truth, many sites don’t need the level of detail or tracking that Google Analytics provides. Alternatives like Fathom (referral link for a $10 discount) makes more sense for site owners concerned with privacy because it:

Offers the information they need (page views, unique page views, referrers, goals)

Doesn’t set cookies or track users

Collects more data (not blocked by ad-blockers or browsers)

Is financed by actual money, not user data

Another example would be the Facebook Pixel. It’s promoted as a way to optimise ad campaigns: it tracks users and sending the data back to Facebook.

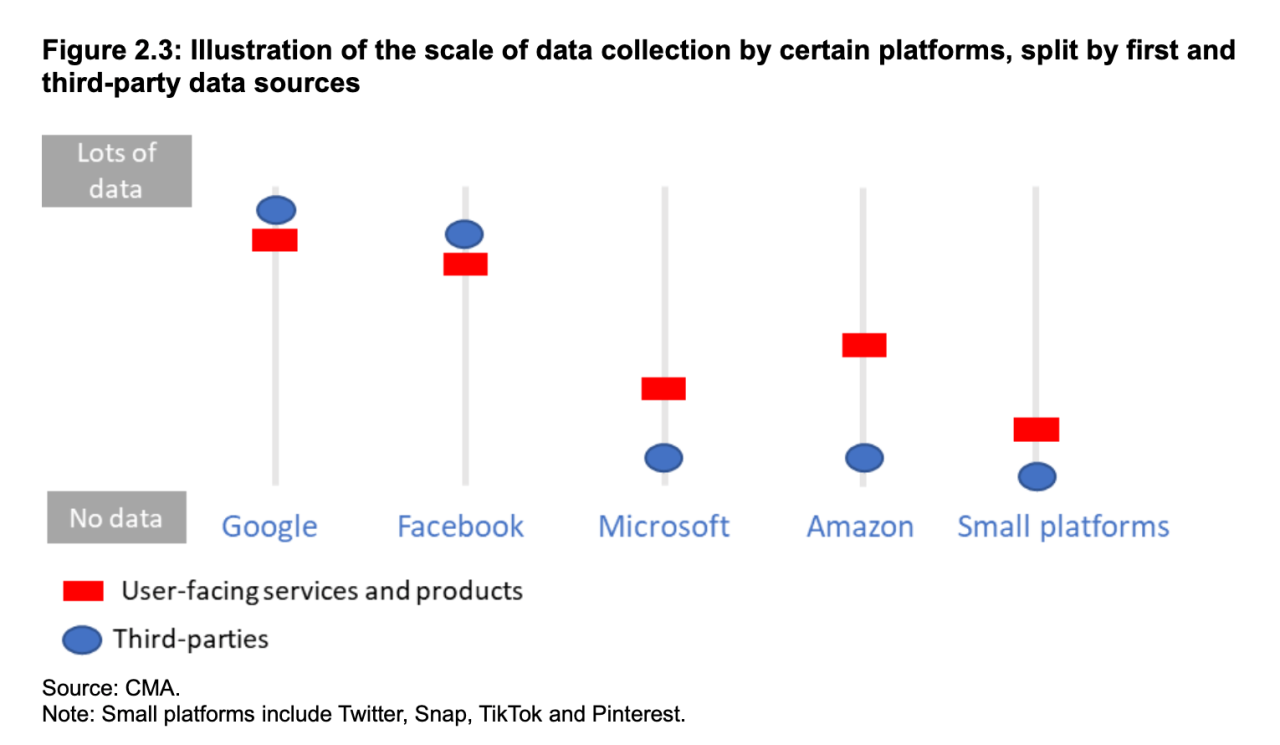

Facebook use the data to inform advertiser’s campaigns and refine behavioural data they collect about individuals, with the ultimate goal of selling more ads. To give you an idea of the scale of data fed back to Facebook through these services, here’s a chart from the UK Competition & Markets Authority’s “Online platforms and digital advertising” market study in July 2020 (Figure 2.3, p50).

In other words: Facebook collects most of its data from third-party websites.

But it’s possible to optimise ads in a privacy-focused way by including referral attributes in campaign links or sending users to unique landing pages. Both of these techniques allow site owners to assess the effectiveness of ads without sending the data back to Facebook.

And for site owners looking to retarget users, mailing lists are a great privacy-focused option. Mailing lists let organisations market:

Straight to a user’s inbox

To an audience they know is interested

Without tracking users

Ultimately, there are often privacy-focused ways to achieve the goals we’re told can only be achieved by tracking users. It doesn’t have to be that way.

Data protection by design

Aside from the metrics we follow, we also need to consider the data we collect. By collecting only necessary data, we build trust with users, reduce exposure to data breaches and improve our website’s user experience (UX).

A good example of this is a mailing list sign-up form, where it’s common to see websites asking for unnecessary information. The form needs to collect the user’s email address: everything else is optional.

If we decide we need to collect other information about a user, we should ask ourselves how important it is. Do we need to know their:

First name? Possibly useful for personalisation.

Last name? May not be necessary in many situations.

Date of birth? Unlikely to be useful outside for many types of site.

Whatever the data, we need to weigh how useful the information is against the impact it has on UX and the additional responsibility of storing that information.

A privacy-focused site would also:

Hold data for the shortest reasonable time

Delete data that’s no longer needed

Where possible, exclude personal information from backups

The privacy-focused approach

Running a website in a privacy-focused manner is a mindset rather than a set of requirements.

Privacy-focused sites follow at least some of these principles:

Value useful data over vanity metrics

Use cookie-less services where possible

Add third-party integrations from companies with a strong privacy track record

Only collect necessary data and delete it when no longer needed

Make it clear what cookies are being used

Don’t set cookies before a user opts-in

Make it easy for users to reject tracking or opt-out (emails, cookies, etc)

Privacy is a broad topic. Taking a privacy-focused approach to building a site needs planning and care, but there are lots of benefits to this approach.

Designing privacy into a site reduces exposure to data breaches: you can’t leak what you haven’t collected. But there are clear UX benefits, too.

In some cases, these approaches might mean a site doesn’t need a cookie banner. Forms will be shorter and users are less likely to think, “why do they need to know [X] about me?”.

Then there’s performance: marketing scripts are famed for making sites slow. Reducing or removing these keeps sites zippy, which is also good for SEO.

Cookie-less analytics can collect more of the core data you need. As cookies and other trackers aren’t blocked, you’ll have a better idea of your site’s traffic, referral sources and page conversions.

Reducing your site’s reliance on Google and Facebook is good for business. As Rand Fishkin wrote, they aren’t reliable in-your-corner partners.

Google famously kills off projects at an alarming rate. Facebook tout themselves as the champions of small business but that’s a thinly-veiled cover for protecting their core business model.

Building a business without relying on Google and Facebook increases the business’ resilience. If you need to use their services, you’ll be in a much stronger position to make the best of them.

And finally, taking a privacy-focused approach creates trust with users. Each change is a small step, but the combined effect is likely to be a fast site without many of the UX issues typical of sites that utilise privacy-invasive practices.